The groundwork for the concept of luso-tropicalism was developed by the Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre (1900–1987) in a trilogy of books comprising The Masters and the Slaves, The Mansions and the Shanties, and Order and Progress. Though these books were published from 1933, the term ‘luso-tropicalism’ itself was coined later, in the 1950s, in order to encapsulate Freyre’s series of connected claims about Brazil and Portuguese colonialism.

The key dimensions of the concept are outlined in The Masters and the Slaves. Running through the book is the suggestion that extensive ‘miscegenation’ in Brazil involving people of European, African and (native) Amerindian ‘stock’ had created an ‘admixture’ of subtle and complex gradations. The causes of this were bound up with the Portuguese colonists’ decision to create a sugar monoculture on the latifundist model over which they, a small and predominantly male settler population, would preside. A lack of labour power was used by the colonisers to justify enslavement of, and miscegenation with, the native Amerindian population who were succeeded by African slaves once the former’s nomadic culture had been destroyed by the Portuguese insistence on settled ranches and fixed labour.

The three-way mixing of what was understood in racist pseudoscientific terms as ‘biological stock’ (Freyre describes ‘outback’ communities comprising Amerindians and escaped African slaves) corresponded with a blending of culture so profound and pervasive that little remained of the original group culture (especially when compared to the way that such tightly-defined cultures could be identified and distinguished in the United States). Freyre contended that the history of the Iberian peninsula had predisposed Portuguese settlers to biological and cultural mixing, as well as a governing ethos that he claimed was more benevolent than that found in British or French colonies. Indeed, because of the topsy-turvy dynamic between Portuguese and Moorish culture and its centrality to the peninsular experience, the forms of Portuguese culture that arrived with settlers in Brazil were already hybridised in terms of modes of production and governance, religion, gender roles and sexuality. Another factor was the Iberian peninsula’s warm climate, which meant Portuguese colonists would be prepared for the hot weather that greeted them in Brazil.

Despite Freyre falling under the spell of cultural anthropologist Franz Boas while studying at Columbia in the 1920s, luso-tropicalism – much like the concept of hybridity – works across the registers of biology and culture. So, while Freyre differentiates between the cultures and civilizations borne by the numerous African groups who had been forcibly brought to Brazil – claiming that people from regions of Africa deeply penetrated by Islam were superior in cultural terms to both native Amerindians and the majority of Portuguese settlers, for example – in other places he falls back on notions of biological difference in elaborating on the distinctiveness of given collectives. His account of the rhythms and textures of Brazilian ‘family life’ (a euphemism in itself) is emphatically male and racially inflected, in some instances shading into outright racism.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, responses to Freyre’s elaboration of the concept have been mixed. During the authoritarian rule of Getúlio Vargas, luso-tropicalism provided the inspiration for the idea of Brazilian ‘racial democracy’ and related notions of national identity. Conversely, in his book The Negro in Brazilian Society (1965) Florestan Fernandes set about highlighting the sharp, US-style racial divisions and associated forms of discrimination that characterised life for ‘Afro-Brazilians’ in Sao Paulo. Perhaps the most telling testimonial to the concept has been its use by governing elites, not only in Brazil but also Portugal, where in the 1960s the government sought to ward off calls for independence from Portugal’s African colonies by introducing reforms premised on Freyre’s work.

In conclusion, luso-tropicalism is an attempt to spin a unitary narrative out of a series of unequal encounters, forced migrations and patterns of living ordered by the priorities of Portuguese settler colonialism – a story that would be elevated to the level of national (and civilizational) identity. It reminds us that attempts to reckon with racial mixing in the context of national identity have a long, and perhaps underexplored, history, while also underlining the need to scrutinise accounts that celebrate and romanticise ‘mixedness’ as something inherently progressive.

Essential reading

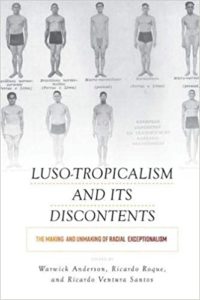

Anderson, W., Roque, R. & Ventura Santos, R. (Eds.) (2019) Luso-Tropicalism and its Discontents: The Making and Unmaking of Racial Exceptionalism. Oxford & New York: Berghahn.

Fernandes, F. (1970) [1965] The Negro in Brazilian Society. New York & London: Columbia University Press.

Freyre, G. (1946) [1933] The Masters and the Slaves. New York, NY: Knopf.

Freyre, G. (1963) [1936] The Mansions and the Shanties. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Freyre, G. (1970) [1959] Order and Progress. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Further reading

Araujo, A. L. (2015) ‘The mythology of racial democracy in Brazil’. Open Democracy, June 22.

Celarent, B. (2010) ‘Book review: The Masters and the Slaves. By Gilberto Freyre’. American Journal of Sociology, 116(1): 334-339.

De Almeida, M. V. (2008) ‘Portugal’s Colonial Complex: From Colonial Lusotropicalism to Postcolonial Lusophony’. Paper presented to Queen’s Postcolonial Research Forum, Queen’s University, Belfast, April 28.

Questions

What are the central characteristics of luso-tropicalism?

Can you situate Freyre’s work in the context of the ‘nature versus nurture’ debate that raged in the first half of the twentieth century?

How has luso-tropicalism been used by governing elites in Portugal and Brazil?

What do luso-tropicalism and related ideas like racial democracy tell us about the relationship between ‘race’ and national identity?

Submitted by James Rosbrook-Thompson

As a recent recipient of the graduate school certificate in African studies at ASU, my final drew from or focused in part on the settler narrative movement of the antebellum era. Despite the discovery of over 100 burials from this era that came to light recently, it was all treated in a quite troubing manner. Settler Colonial mentality was pervasive. It is clear, the slave labor narrative must be preserved at all cost. Local professional organizations and offices were disrespected and ignored as if the descended community did not exist. People wear the continuance of mixed relationships from this history and it is only now that they are finding their voice and their heritage in some cases. Global social theory is spot on.

I’m interested in colonialism,settler colonialism and decolonisation as it speaks to the original ownership of the land/country[?].

I was interested to read ‘the tendency among some scholars of settler colonialism to treat settlement as inevitable, simultaneously relieving settler societies and states of the burden of reconciling with indigenous peoples, and placing the burden of accommodating settler sovereignty onto those same indigenous peoples'[above]

I have been tentatively searching for references to the morality/legality of colonialisation,which could possibly have huge ramifications,and they are scarce.

Interesting. Could you please add Maria Lugones’s work in the further reading section please? She not only engaged with Quijano’s concept but revised it significantly to demonstrate the coloniality of gender. Thank you.