‘Unlike the history of Western (white, middle-class) feminism, which has been explored in great detail over the last few decades, histories of Third World women’s engagement with feminism are in short supply’ Chandra Talpade Mohanty 2003, 45

Feminism is a movement primarily associated with white Western women’s mobilisations around their rights, historically spanning from suffrage, equal pay through to reproductive and sexual rights. As a consequence of its Western centric focus, the feminist movement marginalised knowledge production by and about women outside of the West. In the past three decades, Western feminisms have been increasingly challenged by a wide array of intersecting feminist strands (such as Black feminism, Chicana feminism, Eco feminism or Islamic feminism) that disrupted its Western-centrism by providing alternative knowledges.

One of the most prominent examples of a challenge to dominant Western feminist perspectives is postcolonial feminism. This has played two key roles in feminist thought. First, it expanded the field of feminist theory to include issues of race and postcoloniality within feminism. Then, it put pressure on mainstream postcolonial theory to acknowledge gender and look towards women’s representation in colonial and postcolonial literature. Postcolonial feminism played a key role in informing Third-wave feminism that emerged in the 1990s. One of the influential texts that laid some foundations for the Third-wave was the Cherrie Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldúa anthology, This Bridge called my Back:

As Third World women we clearly have a different relationship to racism than white women, but all of us are born into an environment where racism exists. Racism affects all of our lives, but it is only white women who can ‘afford’ to remain oblivious to these effects. The rest of us have had it breathing or bleeding down our necks. (Moraga and Anzaldúa, 1981, p.62)

Second-wave feminist assumptions of ‘universal sisterhood’, perhaps most poignantly expressed through Robin Morgan’s much acclaimed book Sisterhood is Global (1984), became an important point of departure for postcolonial and Black feminists that took issue with Second-wave feminist assumptions that Western middle-class women’s experiences were the concerns of all women:

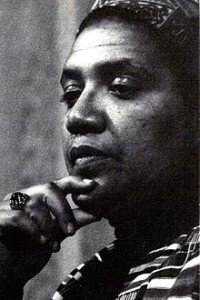

By and large within the women’s movement today, white women focus upon their oppression as women and ignore differences of race, sexual preference, class and age. There is a pretence to a homogeneity of experience covered by the word “sisterhood” that does not in fact exist (Audre Lorde, Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Redefining Difference, 1984, p.116)

By and large within the women’s movement today, white women focus upon their oppression as women and ignore differences of race, sexual preference, class and age. There is a pretence to a homogeneity of experience covered by the word “sisterhood” that does not in fact exist (Audre Lorde, Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Redefining Difference, 1984, p.116)

Amos and Parmar (1984) provided a stern critique of ‘imperial feminism’, urging Western feminism to face up to its inherent racism and racial stereotyping. Postcolonial feminists argued that a certain type of essentialising of women of colour led to the silencing of Black and Third-World women’s experiences, treating them as ‘Others’ within feminist theory. As Trinh T. Min-ha (1989) pointed out, the inclusion of ‘Third-World Women’ in Western feminism often happens instrumentally, for example by token inclusions of one woman of colour in all-white feminist gatherings. Chandra Talpade Mohanty raised attention to Western women producing knowledge on behalf of all by asking: ‘What are the methods used to locate and chart Third World women’s self and agency?’ and ‘Who produces knowledge about colonized peoples and from what space/location? (2003, p.45)’. This is poignantly laid out by Gayatri Spivak in her seminal text ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’ (1988).

These interventions forced white feminists to acknowledge that gender intersects with a variety of social divisions such as race, class and religion and that the concerns of white middle-class women were not universal.

White feminist Adrienne Rich (1984), writing critically about her whiteness, has said that there is an assumption that ‘only certain kinds of people can make theory; that the white-educated mind is capable of formulating everything; that middle-class feminism can know for “all women”’. As Hazel V. Carby wrote a couple of years earlier: ‘The herstory of black women is interwoven with that of white women but this does not mean that they are the same story. Nor do we need white feminists to write our herstory for us, we can and are doing that for ourselves’ (1982:50).

Linked with postcolonial feminism are other feminist movements that provide vastly different perspectives on women’s freedom and liberation, challenging the dominant idea that a Western vision of development rooted in modernity must necessarily be a condition for all women’s liberation. Originating in the 1960s as part of Latin-American and Mexican-American minority rights struggles, Chicana Feminism took off when women started objecting to their role within the Chicano movement and, more generally, to women’s unequal status within the family and the workforce. Chicanas incorporated race and class in their gender politics, as illustrated by a prominent Chicana feminist Gloria E. Anzaldúa, something that did not sit well with the white Anglo Feminist Movement.

Linked with postcolonial feminism are other feminist movements that provide vastly different perspectives on women’s freedom and liberation, challenging the dominant idea that a Western vision of development rooted in modernity must necessarily be a condition for all women’s liberation. Originating in the 1960s as part of Latin-American and Mexican-American minority rights struggles, Chicana Feminism took off when women started objecting to their role within the Chicano movement and, more generally, to women’s unequal status within the family and the workforce. Chicanas incorporated race and class in their gender politics, as illustrated by a prominent Chicana feminist Gloria E. Anzaldúa, something that did not sit well with the white Anglo Feminist Movement.

Another movement that challenges feminist assumptions about non-Western women is Islamic feminism. Islamic feminism originated as a defined movement around the 1990s, although feminism in Islam can be traced back to 1890s. It provided alternative perspectives on some of the key themes in Western feminist theory, such as the public and private divide (Pierce 1993) or the hijab (Mernissi 1991).

A rich variety of feminist voices including Angela Davis, Avtar Brah, Leila Ahmed, Audre Lorde, Fatima Mernissi, Vandana Shiva, bell hooks, Patricia Hill Collins, Trinh T. Minh-ha and Gayatri Spivak among many others have contributed to shape and influence a feminist theory that incorporates ideas about race, postcoloniality, critical whiteness and Western imperialism. These diverse movements have in common a certain diversion away from a centring on white Western women as the subjects of feminist theory.

Essential reading

Lewis, E and Mills, S. (Eds) (2003) Feminist Postcolonial Theory: A Reader Routledge: London

Recommended reading

Lorde, A. (1984) The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches

Lorde, A. (1984) Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Redefining Difference in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches

Mirza, H. S. (1997) Black British Feminism: A Reader, Routledge

Mohanty, C.T. (2003) Feminism Without Borders: Decolonizing Theory, Practising Solidarity, Duke University Press

Mernissi, F. (1991) The Veil and the Male Elite. A Feminist Interpretation of Women’s Rights in Islam, Basic Books

Trinh, T. Min-ha (1989). Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism.

Moghadam, V. (2002) ‘Islamic Feminism and Its Discontents: Toward a Resolution of the Debate,’ Signs, Vol. 27, No. 4 (Summer), pp. 1135-1171

Moraga, C. and Anzaldúa, G. (1981) This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, Persephone Press

Spivak, G. (1988) Can the Subaltern Speak?

Questions

Submitted by Kasia Narkowicz

7 thoughts on “Zapatismo”