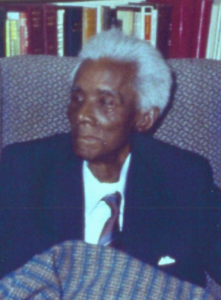

Born in Tunapuna, Trinidad and Tobago to lower middle-class black parents one generation removed from emancipation, C. L. R. James (1901-1989) was a social theorist, historian, writer, and revolutionary whose maturity roughly corresponds to what Eric Hobsbawn called ‘the short 20th century.’ It was this contextual standpoint of a Caribbean childhood, and later movements to Britain, United States, and West Africa, that shaped his view of the destructive complexity of the modern world and the imperative to break with “old bourgeois civilization” (James cited by Grimshaw, 1991)

Born in Tunapuna, Trinidad and Tobago to lower middle-class black parents one generation removed from emancipation, C. L. R. James (1901-1989) was a social theorist, historian, writer, and revolutionary whose maturity roughly corresponds to what Eric Hobsbawn called ‘the short 20th century.’ It was this contextual standpoint of a Caribbean childhood, and later movements to Britain, United States, and West Africa, that shaped his view of the destructive complexity of the modern world and the imperative to break with “old bourgeois civilization” (James cited by Grimshaw, 1991)

In the Global North James is primarily known for two books, The Black Jacobins (1938) which arguably founded Atlantic Studies, and Beyond A Boundary (1963) which influenced the research agenda of late 20th century cultural studies. Each book is indicative of the various wings of James’ wider intellectual project, with the first asking scholars to reconsider the role of racial oppression in capitalism and the second prompting a reconsideration of the role of class formation in popular culture via his treatment of sport, race, and imperialism. These projects combine to provide a Marxist inspired analysis of modernity in which questions of combined and uneven development are foregrounded. The result is to demonstrate the enduring links between advanced capitalist countries and colonized regions along the lines of race, class, and everyday experience.

James’ critique of modernity brought worldwide recognition and broke ground for others to work in this field. But equally important are his thoughts on Caribbean politics and economics, topics of his that receive relatively less attention overall. To begin, through The Life of Captain Cipriani (1932) and The Case for West Indian Self-Government (1932), in the pre-war era he shaped the movements for West Indian independence. (Portions of his archive are preserved at Cipriani College of Labour & Co-Operative Studies in Trinidad and Tobago and still maintained by the local labor movement.) On returning to Trinidad in 1956 after being deported from the United States, James became the editor of The Nation, a local newspaper, famously advocating for Frank Worrell to become captain of the West Indies Cricket Team. This well-known case is but one minor example of how James used the position to revisit fundamental questions about government and society, sensing the significance of the historical moment where West Indians could become the vanguard in the struggle for more egalitarian social relations.

In the post-independence period James took stock of the various contradictions, competitions, and antagonisms that circulated in the social life in the West Indies and suggested that efforts to induce modernization were shortsighted. This put him in conflict with the post-independence political class, whose budding radicalism was tempered and redirected into cultural nationalism. For example, contra the views of notable Caribbean political economists like Sir Arthur Lewis who thought that Caribbean development was hampered by unemployment and a weak local capitalist class, James stressed how prosperity could be achieved through labor taking a greater control of production. Effectively, moving Caribbean societies from an agricultural base to industrialism would likely prove difficult unless there was greater attention to the legacies of colonial governance created by racial capitalism. In summary, for James emancipation can best be achieved through a social reconstruction of the way people relate to one another. Much needed if one were to escape the “problems of nationality.” Sadly, James’ views did not prevail.

Escaping the problems of nationality led James’ to have a significant role in promoting Pan-Africanism, a topic he wrote about in Nkrumah and the Ghana Revolution (1977). Later when reflecting back on this period, he wrote that,

“there were never all told more than a dozen of us, who banded ourselves together in 1935 to propagate and organize for the emancipation of Africa. For years, we seemed, to the official and the learned world, to be at best, political illiterates. Yet we were part of the New World pregnant in their old decay.” (James, Tomorrow and Today, 1)

These words capture so well the many diverse elements of James’ work, like his Marxist reading of history and his contribution of early post-colonial thought rubbed up against the incredulity of the European intellectual class. A committed, practising post-Trotskyist, James’ politics catered towards revolutionary emancipatory impulses, and suggested that gradual improvements of living and working conditions were insufficient. Rather, his politics centred upon the historical and geographic inter-connectedness between societies and the people who live in them. In this respect, James anticipated the value of methodologies that examine the transnational movement of capital and knowledge, goods and people.

James’ contribution to cultural studies in the UK, while significant was comparatively slow to develop. Despite being known in niche academics circles, it was only in the mid-1980s and early 1990s that his scholarly status began to increase through Stuart Hall, Bill Schwarz, and other theorists in the postcolonial turn. Three years before his death, a BBC Arena documentary, C. L. R. James’ First Cricket XI helped cement this recognition. Even so, Jonathan Scott (2018) has recently warned how this canonization courts a misinterpretation where James’ project is framed as “primarily concerned with self-fashioning and cultural identity,” an interpretation clearly at odds with James emphasis on the totality of political life and its historical dimensions. Granted, James’ wide and deep range is hard to capture in a few paragraphs, but there is an analytical urgency to his project, to grasp the whole to ultimately offer a critique of, and remedy to, the partiality of capitalist ideology, while also resisting the established dogmas of mainstream Marxism.

Each year more of James’ work is put in circulation increasing the opportunities for sociologists to engage with all of his writing. The most promising of these comes from his time in America, the creation of and iterations from ‘Johnson-Forest’ Tendency particularly how it created a scaffolding for the interpretive analysis in his later work (see Grimshaw 1991). I suspect James’ importance and contribution to the development of global social theory will only increase in the coming decades. Perhaps aptly so given that more than 80 years after the publication of The Black Jacobins, he remains a companion able to help students and scholars “pioneer into regions Caesar never knew” (2005, 1).

Essential Reading:

James, C. L. R. 2005 [1963]. Beyond A Boundary. Yellow Jersey Press, London.

James, C. L. R. 1989 [1963]. The Black Jacobins. Vintage, New York. [First published in 1938]

James, C. L. R. (nd) Tomorrow and Today: A Vision, New World Journal

Further Reading:

Grimshaw, Anna, 1991. C.L.R. James: A Revolutionary Vision for the 20th Century

Henry, Paget, and Buhle, Paul (eds) 1992. C. L. R. James’s Caribbean, Duke University Press, Durham

James, C. L. R. 1992. The C. L. R. James Reader (edited by Anna Grimshaw) Wiley Blackwell, Oxford.

Robinson, Cedric 1983. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill. Chapter 10

Scott, Jonathan. 2018. The Americanisation of C. L. R. James, Race & Class 60(2)

Online Collections:

C.L.R. James Archive at Marxists.org

Henry Paget on CLR James [YouTube]

Questions:

Discuss the importance of James work to the development of postcolonial critique.

What is the relationship between knowledge and politics for James?

What is the significant of The Black Jacobins to the understanding of the early development of capitalism?

Submitted by Scott Timcke