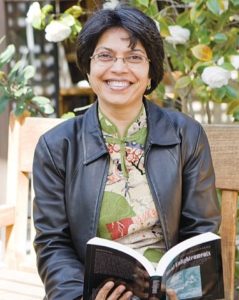

In her relatively short but highly accomplished academic career, anthropologist Saba Mahmood established herself as a scholar who challenged the liberatory, progressive assumptions of feminism and the often-misunderstood logics of Islam. She was born in 1962, in Quetta Pakistan. She came to the United States in 1981 to study at the University of Washington. Mahmood earned her PhD at Stanford University and subsequently joined the faculty at the University of Chicago’s School of Divinity, eventually moving to the University of California, Berkeley, where she became a tenured professor in the Department of Anthropology. Her oeuvre covers an astonishing number of topics, including Islam, secularism, political theory, semiotics, feminism, and philosophy.

In her relatively short but highly accomplished academic career, anthropologist Saba Mahmood established herself as a scholar who challenged the liberatory, progressive assumptions of feminism and the often-misunderstood logics of Islam. She was born in 1962, in Quetta Pakistan. She came to the United States in 1981 to study at the University of Washington. Mahmood earned her PhD at Stanford University and subsequently joined the faculty at the University of Chicago’s School of Divinity, eventually moving to the University of California, Berkeley, where she became a tenured professor in the Department of Anthropology. Her oeuvre covers an astonishing number of topics, including Islam, secularism, political theory, semiotics, feminism, and philosophy.

Mahmood’s first major work, Politics of Piety, combined her rich ethnographic observations of a women’s Islamic revival movement in Egypt with the theoretical work of Michel Foucault and anthropologist Talal Asad. She explored how notions of agency most invoked by feminist scholars, one that locates agency in the political and moral autonomy of the subject, has been brought to bear upon the study of women in patriarchal religious traditions like Islam. She challenges notions of agency and suggests that agency also relates to embodied experiences and means of subject formation and asks, “How do we conceive of individual freedom in a context where the distinction between the subject’s own desires and socially prescribed performances cannot be easily presumed, and where submission to certain forms of (external) authority is a condition for achieving the subject’s potentiality?” The women that she worked with emulated authorized modes of social behavior, which often meant limiting their own individual freedom.

Mahmood’s scholarly contribution becomes all the more important considering her presence on America’s arguably most liberal and progressive campus. Moreover, some of her most prominent interlocutors and colleagues – Judith Butler and Wendy Brown – are themselves at the forefront of feminist and queer theory. The brilliance of Mahmood’s work lies in its success in broadening the argumentative potential of feminist theory while revealing its limitations. She was able to deploy analytic principles often foreign to Islamic sensibilities and epistemologies to reveal why those principles were inadequate in understanding the ways in which women were able to realize their subjectivity by submitting themselves to the will of Allah.

Her later work engaged controversies about blasphemy and the limits of political secularism. In Is Critique Secular? – a collection of essays by Talal Asad, Judith Butler, Wendy Brown, and Mahmood that grew out of a Berkeley symposium on critical theory – Mahmood argues that the normative conception of the European idea of religious liberty privileges belief and conscience at the expense of practices, rites, and rituals. This conception, strongly Protestant in its entailments, is the standard against which other faiths are measured. Her essay’s point of departure was the controversy over Danish cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad. She interrogates why people found it shocking that Muslims were willing to engage in widespread protest and violence over the caricaturization of a holy figure. She writes:

Those who profess love for the Prophet do not simply follow his advice and admonitions… but also try to emulate how he dressed; what he ate; how he spoke to his friends and adversaries; how he slept, walked, and so on… Muhammad, in this understanding, is not simply a proper noun referring to a particular historical figure, but the mark of a relation of similitude. In this economy of signification, he is a figure of immanence in his constant exemplariness and is therefore not a referential sign that stands apart from an essence that it denotes.

In her second solo manuscript, Religious Difference in a Secular Age she argued that instead of creating a more equitable and peaceable society, secularism in Egypt actually had the opposite effect: they agitated and exacerbated interconfessional strife. Secularism is a “statist project” that “aims to make religious difference inconsequential to politics while at the same time embedding majoritarian religious norms in state institutions, laws, and practices.” Her arguments ran up against the liberatory potential of Western-style democracy while remaining unapologetically committed to giving a genuine account of confessional tensions between Coptic Christians and Muslims in Egypt. Mahmood’s work is theoretically and ethnographically honest in the truest sense of the word. She refused to make differences between Islam and the West palatable to liberal aspirations, and she deserves our thanks for that.

In March 2018, Mahmood died after fighting pancreatic cancer, having inspired many students and colleagues in her field to defy their sensibilities, assumptions, and deeply held convictions about religion, gender, and politics.

Essential Readings:

Mahmood, S. (2012). Politics of piety: the Islamic revival and the feminist subject. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press (access to Chapter 1: The Subject of Freedom)

Mahmood, S. (2016). Religious difference in a secular age: a minority report. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press (access to Introduction)

Further Readings:

Asad, T. (2003). Formations of the secular: Christianity, Islam, modernity. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press

Asad, T. (1993). Genealogies of religion: discipline and reasons of power in Christianity and Islam. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press

Taylor, C. (1989). Sources of the self: the making of the modern identity. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press

Questions:

Can we explode the analytic binary, as Mahmood asks us, of oppressed and oppressor in conversations about power?

What other kinds of livelihoods and ways of engaging with the world are possible that these categories are unable to capture?

Is submission to an institution, figure, divinity, or scriptures an authentic way to realize agency and subjectivity? Or is thinking agency as something attainable, indeed desirable, altogether problematic?

Submitted by Shahrukh Khan