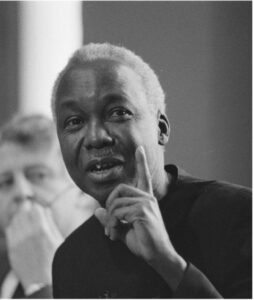

Julius Nyerere was a philosopher, anti-colonial agitator, and teacher who led Tanganyika to independence from Britain in 1961. Endearingly called Mwalimu (“Teacher” in Kiswahili), Nyerere is arguably remembered most for his articulation of Ujamaa philosophy in pursuit of national unity, socialism, and development in Tanzania. Contrary to many other colonized spaces in Africa, Nyerere led Tanganyika to independence without militant anti-colonial struggle.

Julius Nyerere was a philosopher, anti-colonial agitator, and teacher who led Tanganyika to independence from Britain in 1961. Endearingly called Mwalimu (“Teacher” in Kiswahili), Nyerere is arguably remembered most for his articulation of Ujamaa philosophy in pursuit of national unity, socialism, and development in Tanzania. Contrary to many other colonized spaces in Africa, Nyerere led Tanganyika to independence without militant anti-colonial struggle.

He peacefully retired in the mid-80s after ruling as Tanzania’s first President since independence. Simultaneously a scholar and politician, Nyerere’s thinking was always grounded in the practical considerations necessary for leading a newly-independent country such as Tanganyika.

Soon after independence, Nyerere began to theorize what would become his leading political philosophy: Ujamaa, which translates to “African socialism” or “African familyhood.” Ujamaa was based on multiple epistemic currents, including Mao-inspired socialism, European ideas of development and modernisation, and African understandings of community, relationality, responsibility, and unity. Since the vast majority of Tanzanian society was engaged in farming at the time of independence, Ujamaa envisioned the rural space and the agricultural sector to be the motor for development in Tanzania which would ultimately allow the country to catch-up to Europe and its levels of modernisation and leisure-life.

Concerned about continuous imperial control by European powers in the form of economic and financial dependence, a central facet of Ujamaa was the principle of Kujitegemea, or Self-Reliance. Through Kujitegemea, Nyerere articulated the importance of African countries to go beyond political independence to achieve true freedom and decolonization. While this did not mean the rejection of any and all help, it did require the ability of a people to be economically self-reliant and thus determine its own future, a possibility which according to Nyerere would be severely undermined through, for instance, a reliance on foreign loans to generate development.

In addition to rural development, Nyerere understood Ujamaa as a nation-building tool that would bring the highly diverse sectors of Tanzanian society together to form one nation through communal working and living together. Nyerere was fiercely ‘anti-racial’, as he would call it, and rejected any sort of politics that was based on a specific racial, religious, or ‘tribal’ articulation of identity. This reaped critique from more radical sectors of Tanzanian society which were concerned about the continued presence of European administrators in key political, military, and advisory positions of Nyerere’s government, begging questions over the actual depth of decolonization.

Ujamaa’s most concrete manifestation was Ujamaa Vijijini, Nyerere’s villagization project which began in the 1960s as an effort to organize Tanzania’s rural population in villages where people would work and live together. Nyerere emphasized that development, villagization, and socialism could only be achieved when actively pursued by the people themselves rather than mandated top-down by a government. However, by the late 60s and early 70s top members of his party (TANU) grew increasingly impatient with the slow pace at which villages were formed, forcing Nyerere to depart from his initial vision to pursue a more authoritarian strategy for villagization.

Nyerere was also a committed Pan-Africanist. His idea of Pan-African unity was one of gradual rather than radical integration as pursued by other Pan-African leaders such as Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah. Nyerere stressed the importance of nation-building and regional integration before continental unity. While he fell short in realizing this vision, the unification of Tanganyika and Zanzibar to form Tanzania shortly after independence in order to contain superpower influence is one manifestation of Nyerere’s Pan-Africanism that remains until today.

Throughout his roles as anti-colonial leader and President, Nyerere’s thinking was always marked by a deep concern for the condition of Tanzanians and how to realize development, national unity, and socialism. Nonetheless, much of his radical thinking remained trapped within developmentalist ideologies, colonial paternalism, and modernization aspirations whereby Europe remained the horizon to which Tanzania must “catch-up.” Hence, there are outstanding questions about the depth of decolonization achieved by Nyerere, not least on legal-administrative and epistemic levels, which should be carefully examined together with his remarkable achievements and praxis-oriented thought.

Essential Reading

Nyerere, Julius (1967) “The Arusha Declaration and TANU’s Policy on Socialism and Self-Reliance”

Nyerere, Julius (1962) “Ujamaa – The Basis of African Socialism”

Further Reading

Nyerere, Julius K. (1968) Ujamaa – Essays on Socialism. London: Oxford University Press.

Nyerere, Julius K. (1968) Freedom and Socialism: A Selection from Writings and Speeches, 1965-1967. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bjerk, Paul (2017) Julius Nyerere. Athens: Ohio University Press.

Shivji, Issa, Saida Yahya-Othman and Ng’wanza Kamata (2020) Julius Nyerere – A Biography: Development as Rebellion. Dar es Salaam: Mkuki na Nyota.

Questions

Where in Nyerere’s Ujamaa philosophy do you identify a reproduction of colonial thought and Eurocentric visions?

How does Kujitegemea relate to understandings of sovereignty, both on a theoretical level as well as in its articulation through contemporary social movements (e.g. Indigenous sovereignty or food sovereignty)?

What lessons do we learn from Nyerere’s villagization project for decolonial projects today?

How should we reflect on Nyerere’s strategy for Pan-African unity in light of contemporary Pan-African projects?

Photo Credit: “File:Bezoek president Nyerere van Tanzania president Nyerere spreekt in de Eerste Ka, Bestanddeelnr 933-2627.jpg” by Rob Bogaerts / Anefo is marked with CC0 1.0

Submitted by Felix Mantz