Over the last decade or so, the term racial neoliberalism has been used in an effort to determine the relationship between racism and neoliberalism in the present conjuncture. Moreover, this term has been used by scholars to explore a diverse range of topics such as:

Over the last decade or so, the term racial neoliberalism has been used in an effort to determine the relationship between racism and neoliberalism in the present conjuncture. Moreover, this term has been used by scholars to explore a diverse range of topics such as:

- Black politics (Enck-Wazner, 2011: Cohen, 2017);

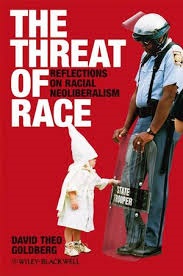

- Changing social formations of race (Goldberg, 2009);

- Securitisation and the ‘war on terror’ (Kapoor, 2011);

- State repression and refugee governance (Bhagat, 2019);

- Restorative justice (O’Brien & Nygreen, 2010);

- Food justice (Sbicca & Myers, 2016)

- Militarism, corporatism and the evolving nature of capitalism and socio-economic and politico-cultural relations (New Dawn, 2018); and,

- Racism in education (Giroux, 2010) and sport (Burdsey, 2014).

The term neoliberalism is generally used to mark the shift away from the socio-economic and political-cultural values, relations and processes of the post-Keynesian era (see Gahman and Hjalmarson’s entry on neoliberalism), and a turn to forms of economic and political thought and governance which place emphasis on free markets, free trade, strong property rights, privatization and individual responsibility.

In the name of free markets and free trade, deregulation and privatization are seen as being a means by which entrepreneurialism can be unshackled. This involves reconfiguring the role of the state whereby the state withdraws from certain areas of social provision (e.g. healthcare, welfare and social services), yet continues to play a critical role in establishing and guaranteeing certain institutional, socio-economic and socio-political conditions.

Critiques of neoliberal development theory have traced the enduring impact of the racial logics that once underpinned European sovereignty and democracy while at the same time legitimising slavery and colonial expansion, through to the forms of extraction, exploitation, dispossession and appropriation of present-day neo-colonialism (see Cornelissen, 2020).

The recently launched Connected Sociologies Curriculum Project also addresses this question in its short course on ‘Colonial Global Economy’. In fact, contributors draw attention to the ‘colonially-instituted arrangements and relationships’ which continue to endure today, such as international economic law and specific labour regimes in global supply chains. Indeed, it might be argued that as the role of the state in the Global North has been reconstituted, neoliberalism in the Global South has enabled supranational financial institutions such as International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the World Trade Organization to play a powerful role in regulating and facilitating global trade and finance. So much so, the aforementioned institutions and more powerful, wealthy states and have been able to undermine postcolonial sovereignty.

When it comes to explaining the current arrangement of things, Gahman and Hjalmarson point out that the present social conditions are said to be the result of either individual and/ or an aggregation of individual choices. Gahman and Hjalmarson also point out that the individual has been encouraged to ‘monetize convert their individual capabilities, passions and desires for the goal of financial self-capitalisation and attainment of individual recognition’. The neoliberal era has also been one in which a certain types of subjectivities have been constructed in an attempt to regulate social life by controlling both the consciousness and bodies of the population. This includes reconfiguring the relationship between individuals and the body politic by nurturing anxiety as a mode of self-governance. Discourses of risk have also been used as a way of advancing certain ideals such as rational choice and individual responsibility, thus leading to forms of risk management aimed at shifting responsibility away from the state onto the shoulders on the individual. For David Chandler and Julian Reid, these conditions have led to the emergence of a ‘degraded subject’ who, on the one hand, is said to have acquired greater adaptability and resilience, but has simultaneously experienced their erosion of their autonomy and agency.

As neoliberal logics and practices have become hegemonic over recent decades, the term racial neoliberalism has been used to explain the emergence of common-sense understandings and discourses as to what actually constitutes racism. More specifically, the influence of neoliberalism’s signature motifs – namely, individualism, personal choice, responsibility and meritocracy – has been such that racism is often reduced to being either a thing of the past, an aberration and/ or merely individual prejudice. In this context, racism is commonly been conceived as being illiberal, overt, intentional, violent and the reserve of extremists. The emphasis placed on individual choices, responsibility and ‘risky’ behaviour has also formed part of a discursive strategy aimed at limiting the discussion of racism as a legitimate and meaningful topic of public discussion (Enck-Wazner, 2011: 24). Thus, obscuring the systemic nature of racism, while limiting the purchase of the idea that racism and public policy are central to the maintenance and reproduction of structural inequality (Lentin and Titley, 2011: 168).

In this context, citizenship has also been reconstituted as a technology of governance, as opposed to being a ‘universal’ status that confers rights and protections. In the context of the ongoing Windrush scandal and the refugee crisis, we might think of the way in which the neoliberal goal of ‘opening up’ borders for the purposes of free trade runs parallel to discourses, policies and the construction of citizenship whereby states are entrusted with the creation of ‘waste humans’ (Tyler, 2013) both within and at the borders of sovereign territories. Rather than being framed as a result of neoliberal political and economic governance, we live in a time where precarious subjects are both positioned at the centre of social explanation and framed as the cause of social problems.

Essential Readings

Bhattacharyya, G. (2013) ‘Racial Neoliberal Britain?’, in Kapoor, N., Kalra, V. and Rhodes, J. (eds.) The State of Race. London: Palgrave-Macmillan.

Goldberg, D. T. (2009) The Threat of Race: Reflections on Racial Neoliberalism. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Giroux, H. (2008) Against the Terror of Neoliberalism: Politics Beyond the Age of Greed. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Mondon, A. and Winter, A. 2020. Reactionary Democracy: How Racism and the Populist Far Right Became Mainstream. London: Verso.

Further reading and resources

Lentin, A., & Titley, G. (2011) The Crises of Multiculturalism: Racism in a Neoliberal Age. London: Zed Books.

Enck-Wanzer, D. (2011) ‘Barack Obama, the Tea Party, and the Threat of Race: On Racial Neoliberalism and Born Again Racism’, Communication, Culture and Critique, 4 (1): 23-30.

Cohen, C. (2017) ‘From Ferguson to Flint: Race, Neoliberalism and Black Politics Today’, Reflections on African American Studies: The Department of African American Studies, Princeton University – video.

Kelley, R. G. (2016) ‘Over the Rainbow: Second Wave Ethnic Studies Against the Neoliberal Turn’, University of California Television – video.

New Dawn. (2018) ‘Expropriation, Exploitation, and the Neoliberal Racial Order – Michael C. Dawson’, Anchor – podcast.

Tyler, I. (2013) Revolting Subject: Social Abjection and Resistance in Neoliberal Britain. London: Zed Books.

Questions

Discuss the main features which characterise racial neoliberalism.

What does the term racial neoliberalism tell us about the relationship between racism and capitalism?

With reference to the term racial neoliberalism, compare and contrast the socio-economic and political-cultural relationships in the Keynesian and post-Keynesian eras.

Critically examine the role of the state in facilitating racial neoliberalism.

Consider the ways in which, if any, neoliberal logics and thinking have fed into discourses of post-racialism.

Submitted by Stephen D. Ashe

7 thoughts on “Zapatismo”