“Tell no lies. (…) Claim no easy victories”

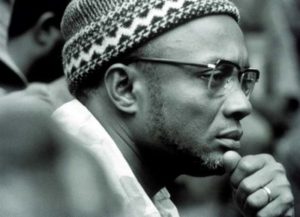

If there was ever such a thing as a practical philosopher, then Amílcar Cabral would have stood as one of the first of such kind. Amílcar Cabral, born in 1924 in Cape Verde and assassinated in 1973, is remembered first and foremost as the leader of the liberation wars in Cape Verde and Guiné Bissau. A brilliant strategist, diplomat and guerrilla tactician, Amílcar Cabral was further notable for his profoundly humane and uniquely independent political vision. Though frequently approached as a thinker through his published speeches, it is difficult to assemble a picture of Cabral’s thought with no reference to his life, and the gestures with which he filled it (c.f. Chabal, 1983).

Born in Guiné-Bissau and raised in Cape Verde, Cabral’s childhood was marked by both a love of learning and the witnessing of colonial injustices, in particular during the 1940s drought and famine (c.f. Villen 2013). In 1945, earning one of very few scholarships of its kind, Cabral secured a place to learn agronomy in Lisbon. The next seven years in the ‘Metropolis’ would be highly significant for Cabral in that it would provide access to the writings of pan-Africanist cultural/political movements; as well as with connections with fellow lusophone African students (e.g. Mario de Andrade, Marcelino dos Santos, Agostinho Neto). It would be during these years, and under the guise of the ‘Centre for African Studies’ in Lisbon, that all important bonds would be forged between key figures of the liberation struggles in Angola and Mozambique. Deeply impressed by Leopold Senghor’s and Aimé Cesaire’s Négritude as well as by Nkrumah’s political visions, Cabral’s emphasis on the need for re-Africanisation had its root at this time (see Rabaka, 2015). Parallel to this influence, Cabral would also be introduced to Marxist ideas, ideas he would use during the liberation struggles in a strongly pragmatic, creative and anti-dogmatic way. Lastly, but also significantly, Cabral’s seven years in Portugal made him deeply sensitive in his position towards Portuguese people. Retaining a position of open-heartedness and kindness to what he saw as misguided people, Cabral quickly identified Portuguese fascism and its renewed imperialist discourse as the greatest source of immediate political evil.

Returning to Guiné-Bissau in 1952, Cabral was engaged by the colonial Forestry and Agricultural civil service. In this role he would conduct a comprehensive census of the country, awarding him with a deep engagement with the social, environmental and economic conditions of Guiné. At this time, Cabral also began his political work mobilizing local populations to demand for a better status. This was soon noticed and culminated in the Colonial Governor asking for him to be ‘transferred’. Unwittingly, this would lead Cabral to further radicalise his struggles. Returning to Lisbon, Cabral found work, which, for five years, would send him on long missions in Angola. In these missions, Cabral would quickly tap into the underground networks agitating for liberation. Involved simultaneously in the underground anti-colonial networks in Lisbon, Cabral would in 1955 participate in the Bandung Conference. This participation, though poorly documented, is crucial to understanding Cabral’s emphasis on diplomatic mobilization as part of decolonial struggles. This mobilization was both in terms of coordinating and uniting anti-imperial struggles as well as mustering international legitimation and support. In Cabral’s own life, this was born out in uniting Lusophone African struggles under a common front as well as by tirelessly working on garnering diplomatic and popular support for Guinea’s liberation war (c.f. Gliejeses 1997, Dadha 1995).

Galvanized by the international momentum against (neo-)colonialism, Cabral would, in 1956, establish the African Party for the Independence of Guiné and Cabo Verde (PAIGC). Having spent the first years doing political work in Guiné’s cities, PAIGC would after 1959 focus its efforts on the countryside. By 1963, PAIGC began its armed guerrilla insurgency and within ten years achieved control over most of Guiné’s territory and declared independence. Supremely successful in terms of guerrilla warfare, Guiné’s liberation was in no small part due to Cabral’s leadership and foresight into grassroots politics, diplomacy and livelihood improvement. Most significantly, in Cabral’s life, insurgency emerged as the most fertile site for theory. Drawing on practical problems in the politics and logistics of insurgency, Cabral regarded insurgency as the key context in which to conceive and form an African nationalism that would succeed in overcoming colonial legacies. In Cabral’s thought, national liberation relied on a unique process of cultural renovation, whereby military struggle would be actively subsumed under a deeper form of struggle towards the re-signification of local non-European cultures and the formation of social forms shorn of colonial subconscious. Indeed, such was Cabral’s insistence on this, that Paulo Freire saw his pedagogical attitudes as uniquely inspiring (c.f. Pereira and Vittoria, 2012).

A man of action more than words, Cabral’s theories seem to be still fully understandable by reference to the extraordinary events of the liberation insurgency of Guiné-Bissau. Assassinated in 1973, before the fall of Portuguese fascism and colonialism, Cabral’s death left a tragic absence, a foreclosure, in the construction of independence in lusophone Africa. Remembered as a moral paragon and political giant in the African liberation wars, Cabral continues to lack the scholarly appreciation his life and work deserves. Engaging with Cabral, however, remains a worthy, necessary and empowering project. In his poetry, in his speeches, in his party archives and in the oral memories of his life, Cabral offers a uniquely visionary and sensitive approach to the historical task of decolonisation. Living beyond the grave, Cabral’s incisive, humane, and pragmatic voice may well continue to teach us – if only we listen.

Amílcar Cabral’s recorded speeches can be viewed here, here, and here.

Questions:

What was Cabral’s understanding of culture in the context of decolonial struggles?

What lessons can be taken from Cabral’s way of theorizing?

ESSENTIAL READINGS:

Cabral, Amilcar. Resistance and Decolonization. Translated by Dan Wood. Rowman & Littlefield International, 2016.

Cabral, Amilcar. Unity and Struggle: Speeches and Writings of Amilcar Cabral. (preview) Monthly Review Press, 1979.

Cabral, Amilcar. Return to the Source: Selected Speeches of Amilcar Cabral (pdf) Monthly Review Press, 1973.

FURTHER READINGS:

Sousa, J. S. Amílcar Cabral (1924-1973): Vida e morte de um revolucionário africano. Lisboa: Nova Vega, 2013.

Chabal, P. Amilcar Cabral: Revolutionary Leadership and People’s War. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

Davidson, B. No Fist Is Big Enough to Hide the Sky: The Liberation of Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde: Aspects of an African Revolution. Zed Books. 1981.

Mario de Andrade, Amilcar Cabral : essai de biographie politique, F. Maspero, Paris, 1980.

Villen, P. A crítica de Amílcar Cabral ao colonialismo: Entre a harmonia e a contradição. São Paulo: Expressão Popular. 2013.

Manji, F. & Fletcher B. (Eds) Claim No Easy Victories: The Legacy of Amilcar Cabral, Codesria. 2013

Rabaka, R. Concepts of Cabralism: Amilcar Cabral and Africana Critical Theory. Lexington Books. 2014

Gleijeses, P. ‘The First Ambassadors: Cuba’s Contribution to Guinea-Bissau’s War of Independence’ , Journal of Latin American Studies, 29:1, 45-88. 1977

Dhada, M. ‘Guinea-Bissau’s Diplomacy and Liberation Struggle’ , Portuguese Studies Review, 4:1, 20-36. 1995

Pereira, A. A., & Vittoria, P. The liberation struggle and the experiences of literacy in Guinea-Bissau: Amilcar Cabral and Paulo Freire. Estudos Históricos (Rio de Janeiro), 25(50), 291-311. 2012

Abdullah, I. ‘Culture, consciousness and armed conflict: Cabral’s déclassé/(lumpenproletariat?) in the era of globalization’, African Identities, 4:1, 99-112. 2006.

Additional Video Sources:

‘Cabralista’ Documentary Series (2011-). see here

BBC Four section on Cabral’s African War, see here

Submitted by António Ferraz de Oliveira