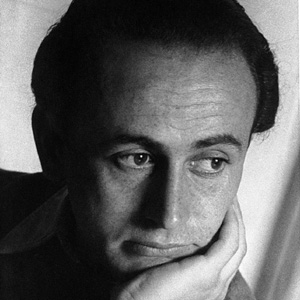

The life of Paul Celan (1920-1970), born Paul Antschel, was marked by tragedies that would come to have a decisive influence on both his character and the mythical poet he would become. Born in the immediate aftermath of the breakup of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Celan grew up in the liberal town of Chernivtsi, the capital of Bukowina. The town situated at the edge of Empire had benefitted from the legacy of Franz Joseph’s liberal attitude towards Jews. The Jewish population comprised half of the town which, because of its rich cultural and cosmopolitan life, had acquired the nickname ‘Little Vienna’. The town’s intellectual and progressive environment allowed Celan to become acquainted with different languages and cultural traditions at a very early age. It was however primarily through his mother’s love for literature, especially the German tradition, that the young Celan cultivated an appreciation for the works of Shakespeare, Schiller, Rilke and Goethe, among various other European poets and literary giants. Although exposed to and fluent in multiple languages (translating the works of no less than 43 poets in his lifetime), Celan adopted High German, the language in which his mother had culturally raised and loved her only child, as his ‘mother tongue’.

During the Shoah, both of his Hasidic parents were deported to labour camps in German-occupied Ukraine, ironically the place from which many Jews had fled in fear of the ruthless Pogroms of the 19th century. His father soon died from Typhus, while his mother was shot in the neck by a Nazi officer. It was especially the loss of his mother which would come to affect Paul Celan the most. In his early poetry, written in the period after her passing away, he would directly speak to his mother (Mutter).

Still do the southerly Bug waters know,

Mother, the wave whose blows wounded you so?

….

Can none of the aspens and none of the willows

allow you their solace, remove all your sorrows?

….

And can you bear, Mother, as once on a time,

the gentle, the German, the pain-laden rhyme

(Celan in Felstiner 2001: 49)

The loss of his mother turned him into a poet that found himself in a permanent state of conflict with his own language. The German language changed from being his mother tongue [Muttersprache] to also the tongue of his mother’s murderers [Mördersprache] (Buck 1993). After having served time himself in a labour camp, Celan moved to Bucharest and Vienna, before eventually settling in Paris. Despite the travelling geographies and his sensitivity for Russian, French, Romanian, Greek, Hebrew and Yiddish, Celan never definitively parted from his mother’s German. There seemed for him no choice but to confront the German language. He once confided to a close friend that “[o]nly in the mother tongue can one speak one’s own truth, in a foreign language the poet lies” (Celan in Joris 2005: 16). Celan tried to salvage, transform and redeem German, confronting the murderers in their own language, while in search of finding his own. Bambach (2013: 21) writes that his “poems attempt to bring to language the limits of the unsayable, pushing against the boundaries of speech in an effort to mourn the numberless in the name of what Derrida would call a “justice of the impossible.” In his 1958 Bremen Prize Speech, Celan explained:

It, the language, remained, not lost, yes, in spite of everything. But it had to pass through its own answerlessness [Antwortlosigkeiten,], pass through frightful muting, pass through the thousand darknesses of deathbringing speech [todbringender Rede]. It passed through and gave back no words for that which happened; yet it passed through this happening. Passed through and could come to light again, “enriched” by all this. In this language I have sought, during those years and the years since then, to write poems: so as to speak, to orient myself, to find out where I was and where I was meant to go, to sketch out reality for myself [um mir Wirklichkeit zu entwerfen] (adjusted from Celan in Felstiner 2001: 395).

Few thinkers or even poets can be said to be so involved and as scrupulously exact in their language as Celan. His trust in the ability of language to disclose truth is perhaps only matched by that of the philosopher Martin Heidegger, for whom language is the “House of Being”. Heidegger argued that the task of poetry resides in exercising its revelatory ability to uncover the truth of the world. Heidegger put his faith in the poet, often more than in the philosopher, to transcribe what the ancient Greeks called Aletheia in human language. For Heidegger all art aspired to the condition of poetry [dichtung], “which demands of us a transformation in our ways of thinking and experiencing, one that concerns being in its entirety” (in Bambach 2013: 1). Writing on Rilke’s The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, he (Heidegger 1988 [1927]: 171, 172) observes:

Poetry, creative literature, is nothing but the elementary emergence into words, the becoming-uncovered, of existence as being-in-the-world. For the others who before it were blind, the world first becomes visible by what is thus spoken.

Celan was first introduced to Heidegger’s work in the late 1940s but initially refused to engage with the thoughts of the former Nazi sympathiser. When he did, however, “he became so intrigued with the thinker’s world that he entered into an imaginary conversation with Heidegger – sometimes friendly, sometimes dissenting – that underlay much of his thinking about poetry and entered into a number of his poems” (Lyon 2006: 7). Celan engaged throughout his lifetime with over a 100 philosophers “but Heidegger’s pre-eminence among all the thinkers in the poet’s library is conspicuous” (ibid.: 10).

However, his ambivalence towards Heidegger’s past tempered his desire to meet the Swabian in person. The unlikely duo, one a Holocaust survivor and the other a former member and apologist of the National Socialist Party, would over a period of almost 15 years exchange letters, poems, thoughts and even moments of care. Throughout this time, Celan’s poetry both borrowed and critiqued Heidegger’s thoughts on language and poetry. He considered him his “vis-à-vis” (Gegenüber) (ibid.).

The two would finally meet in 1967 in Todtnauberg, in the heart of the German Black Forrest, where Heidegger invited the poet for a conversation in his famous mountain hut from where he wrote the 20th century opus magnum Being and Time. The emotionally hypersensitive Celan was at the time on leave from a psychiatric clinic in Paris to read his poetry at the University of Freiburg. Celan’s unstable mental condition and his longstanding distrust for anything associated with Nazism did not discourage Heidegger from inviting him in ‘the hut’ [die Hütte]. Heidegger writes to a colleague responsible for organising the meeting:

I’ve wanted to become acquainted with Paul Celan for a long time. He stands farthest in the forefront and holds himself back the most. I know all of his works, also of the serious crisis from which he managed to extricate himself as much as a person is able. (Heidegger in ibid.: 162).

Concrete details of the encounter and the conversation that ensued are at best sketchy. The meeting was, according to the only observer, the driver, characterised by long painful silences and Celan’s waiting for Heidegger’s atonement of and condemnation for the thinker’s troubled past. Indeed, it is clear without a doubt that “Celan expected from Heidegger a clear, public condemnation of Nazi ideology and an energetic, public warning against its re-invigoration at the time of their visit” (Hart and Hamacher 2011: 20). It remains until this day unclear if that is what Celan received from Heidegger. All that materially remains of the meeting of opposites are a number of guestbook entries, some letters and Celan’s famous poem written a couple of days after the encounter. In the poem, which chronicles the meeting, he hopes “for a thinker’s word to come, in the heart”.

The 26-verses of the single-sentence Todtnauberg poem – a name which combines death and mountain, recurrent themes in Celan’s poetry – continue to be the subject of intense debate in Europe. Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe (1999: 35, 36) wrote that “[i]t is an extenuated poem, or, to put it better, a disappointed one. It is the poem of a disappointment; as such, it is, and it says, the disappointment of poetry.” Jean-Luc Nancy recently contributed a radio essay, entitled “La Rencontre”, (available on YouTube) which discusses Celan’s motives to meet the thinker. “What did he want, he, the Jewish German, from the one who clearly would have to denounce the Nazi enterprise but from whom the text about poetry was a major reference for Celan?” Maurice Blanchot (1989: 479) famously wrote about the meeting that “Heidegger’s irreparable fault lies in his silence concerning the Final Solution. This silence, or his refusal, when confronted by Paul Celan, to ask forgiveness for the unforgivable, was a denial that plunged Celan into despair and made him ill, for Celan knew that the Shoah was the revelation of the essence of the West.”

The two would meet twice more; in June 1968 and in March 1970. Paul Celan committed suicide in the Seine on April 19th, a month after their final meeting. He left an unfinished letter addressed to Heidegger, emphasising the “will to responsibility” that comes with poetry and thought:

Heidegger… that you (by your stance) have decisively weakened that which is poetic and, I venture to surmise, that which is thinking, in the serious will to responsibility of both.[1]

One can only speculate about the exact meaning of Celan’s elusive accusation. My thought is that Celan believed that Heidegger never bore the burden of responsibility that comes from the will to uncover and disclose truth. In contrast, Celan carried the will to responsibility throughout his life on his frail shoulders. The thinker and the poet shared a will to disclose truth but the will to responsibility to thought and poetry was unequally shared between the two.

[1] In German: [Heidegger… dass Sie [durch Ihre Haltung] das Dichterische und, so wage ich zu vermuten, das Denkerische, in beider ernstem Verantwortungswillen, entscheidend schwächen]

Essential Reading

Felstiner, J. (ed) (2001) Selected Poems and Prose of Paul Celan. New Haven (CT): Yale University Press.

Felstiner, J. (2001) Paul Celan: Poet, Survivor, Jew. New Haven (CT): Yale University Press.

Lacoue-Labarthe, P. (1999) Poetry as Experience. Stanford (CA): Stanford University Press.

Lyon, J.K. (2006) Paul Celan and Martin Heidegger: An Unresolved Conversation, 1951–1970. Baltimore (ML): The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Nancy, Jean Luc. The Encounter (with thanks to Philippe Theophanidis for the link)

Further Reading

Bambach, C. (2013) Thinking the Poetic Measure of Justice: Hölderlin-Heidegger-Celan. Albany (NY): State University of New York Press.

Blanchot, M. (1989) “Thinking the Apocalypse: A Letter from Maurice Blanchot to Catherine David”, Critical Inquiry 15 (2), pp. 475-480.

Buck, T. (1993) Muttersprache, Mördersprache (Celan-Studien). Aachen: Rimbaud.

Heidegger, M. (1988 [1927]) The Basic Problems of Phenomenology. Bloomington (IN): Indiana University Press.

Hamacher, W and H. Hart (2011) “Wasen: On Celan’s ‘Todtnauberg’”, The Yearbook of Comparative Literature 57, pp. 15-54.

Joris, P. (1988) “Translation at the mountain of death”, originally presented at Poetic Thought & Translation Conference at Wake Forest University. Available from: http://wings.buffalo.edu/epc/authors/joris/todtnauberg.html

Joris, P. (2005) “Introduction: “Polysemy without mask” (pp. 3-36). In Celan, P. (ed.) Paul Celan: Selections. Berkeley (CA): University of California Press.

Questions

What did Blanchot mean when he said that “Celan knew that the Shoah was the revelation of the essence of the West”?

Why do you think Celan wanted to meet Heidegger?

What does Celan’s poetry and character tell us about the role of and relationship between the victim and the perpetrator of violence?

What is the relationship between poetry and thought?

Can thought feel? How does it feel?

Submitted by Marijn Nieuwenhuis