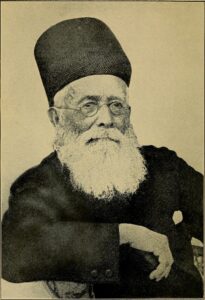

Dadabhai Naoroji (1825-1917) was an Indian scholar, merchant, and politician who was a founding member of the Indian National Congress. Born to a Parsi family in Navsarai in the then-Bombay Presidency (now modern-day Gujarat), Naoroji’s major contribution to the Indian independence movement was his “Drain of Wealth” theory: a detailed analytical study of how the colonial rulers of the subcontinent pillaged its economic resources and shattered its industrial capacity. The theory was most cogently demonstrated in his 1901 work Poverty and Un-British Rule in India. Naoroji was also the first Asian Member of Parliament in the British House of Commons from 1892 to 1895, representing the London constituency of Finsbury Central.

Dadabhai Naoroji (1825-1917) was an Indian scholar, merchant, and politician who was a founding member of the Indian National Congress. Born to a Parsi family in Navsarai in the then-Bombay Presidency (now modern-day Gujarat), Naoroji’s major contribution to the Indian independence movement was his “Drain of Wealth” theory: a detailed analytical study of how the colonial rulers of the subcontinent pillaged its economic resources and shattered its industrial capacity. The theory was most cogently demonstrated in his 1901 work Poverty and Un-British Rule in India. Naoroji was also the first Asian Member of Parliament in the British House of Commons from 1892 to 1895, representing the London constituency of Finsbury Central.

Naoroji’s shock upon witnessing the wealth of Britain during his first visit in 1855 prompted him to develop his economic analysis. Founded on a masterful analysis of the data produced by the Empire, Naoroji used the British imperial state’s own data to prove its historical impoverishment of the subcontinent by mapping Indian net profit alongside different ventures being undertaken by the British Raj. He calculated that there were six major factors to the drain of India’s wealth, which he likened to a “vampirism” that resulted in a yearly loss of approximately £30-40 million with only £250,000’s worth of capital injected back into India per annum (Poverty: p 232).

These six factors were; the Raj was a foreign colonial government, not a representational one; that there was a lack of immigration into India (which, coupled with the lack of capital, stymied the development of any industrial capacity); that the major and miscellaneous expenses of the British army and its colonial civil infrastructure was borne by India and not supported by taxes from the metropole; that India’s resources had been plundered in the name of free trade, and that most income earners were foreign nationals which exacerbated the existing tremendous loss of capital.

Naoroji’s sophisticated analysis was complemented by his oratorical skills, which he displayed on numerous occasions both as a founding member of the Indian National Congress (an organisation whose Presidency he was elected to in 1886, 1893, and 1906) and as an MP for the Liberal Party. His purpose, and that of the wider Congress organisation he belonged to, was, as he put it in a 1901 speech in Whitechapel, “…to make you understand your deficiencies in government, the redress of which would make India a blessing to you, and make England a blessing to us, which it is not, unfortunately, at present.” (Speeches: p 225).

Naoroji’s sophisticated analysis was complemented by his oratorical skills, which he displayed on numerous occasions both as a founding member of the Indian National Congress (an organisation whose Presidency he was elected to in 1886, 1893, and 1906) and as an MP for the Liberal Party. His purpose, and that of the wider Congress organisation he belonged to, was, as he put it in a 1901 speech in Whitechapel, “…to make you understand your deficiencies in government, the redress of which would make India a blessing to you, and make England a blessing to us, which it is not, unfortunately, at present.” (Speeches: p 225).

The “Grand Old Man of India”, as he would become known as, had an enormous impact on the burgeoning independence movement of India. He founded the East India Association in 1866 in London; an organisation that served as the precursor in many ways to the INC, and in front of whom Naoroji first delivered his Drain of Wealth Theory in 1876. He belonged to the “moderate” wing of the INC’s first wave of leaders; men who belonged to the educated “middle class” in the colonial English system and used their skills to produce rigorous systematic critiques of colonialism. Naoroji played a pivotal role in mentoring future moderate INC leaders, like Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, and, of course, Gandhi. In particular, the Grand Old Man’s 1904 declaration of Swaraj (“self-rule”) and conceptions of boycotting English goods as protest and patronising indigenous products via Swadeshi would prove to have a lasting impact.

His material critique made waves outside of India as well. Using the data of the Empire against it silenced the arguments of pro-colonial voices, and gradually shifted public perception in Britain of the role the state was playing in India. It also caught the attention of labour and socialist movements across the world, who invited Naoroji to be part of the Second International in 1889. But, as Rao has remarked, Naoroji’s real contribution to the Indian independence struggle was in providing the raison d’etre of the fight against colonialism. The “Drain of Wealth” Theory was more than a formidable statistical analysis; it was a full-on rejection of British colonial claims to moral legitimacy by demonstrating how it impoverished, not enriched, India and left its inhabitants hungry and destitute.

Dadabhai Naoroji spoke often about how the colonial system of education and laws had a positive impact in the gestation of a new social and legal order within India. But he made it clear that it was no compensation for the poverty unleashed upon the subcontinent as a result of the greed of Britain. Today he occupies but a footnote in the public history of the INC. But his work was critical to providing an intellectual and moral foundation for the Indian freedom struggle, and his economic analysis as a blueprint for other anticolonial movements. In an age where colonial apologists still cling to the facile argument that the British Empire benefitted its colonies, Naoroji’s cutting rebuttal is more relevant than ever.

An official compilation of the remarks Dadabhai Naoroji made during his Parliamentary career can be found here. The INC’s official biographical entry about him can be found here. In 2016, Naoroiji was part of a series of BBC Radio programmes profiling “Great Lives”.

Essential Readings:

Naoroji, Dadabhai 1861. The Parsee Religion. University of London, London.

Naoroji, Dadabhai 1988 (1901). Poverty and Un-British Rule in India. Government of India, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, New Delhi, (First published by Swan Sonnenschein & Co. in 1902).

Naoroji, Dadabhai 1917. Speeches and Writing of Dadabhai Naoroji, ed. GA Nateson & Co., Madras.

Naoroji, Dadabhai 1867. “Observations on Mr. John Crawfurd’s Paper on the European and Asiatic Races,” Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London 5: 127-149.

Further Readings:

Burton, Antionette 2000. “Tongues Untied: Lord Salisbury’s ‘Black Man’ and the Boundaries of Imperial Democracy,” Society for Comparative Study of Society and History: 632-61.

Dasgupta, Ajit K 1993. A History of Indian Economic Thought. Routledge, London and New York.

Masani, RP 1939. Dadabhai Naoroji, The Grand Old Man of India. G Allen & Unwin, London.

Patel, Dinyar 2020. Naoroji: Pioneer of Indian Nationalism. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA.

Rao, Surendra B (2010). “Disrobing Colonialism, and Making Sense of It,” Social Scientist 38 (7/8):15-28.

Thakur, Kundan Kumar 2013. “British Colonial Exploitation of India and Globalization,” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 74: 405-415.

Questions:

What was the significance of Naoroji’s use of imperial state data in formulating his theory?

Discuss the importance that the “Drain of Wealth” theory could have in critical analyses of the historical context of contemporary globalisation?

What was Naoroji’s conception of the role the British imperial state had to play in the freedom struggle, and how did it change?

How did Naoroji’s ideas a) influence future moderate INC leaders and b) the radical non-INC freedom movement leaders?

Submitted by Aditya Iyer