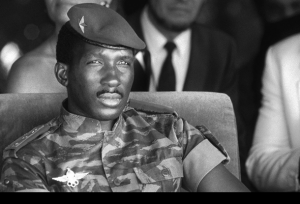

Thomas Sankara (1949-1987) was unique among late 20th century presidents in Africa and beyond. His political leadership was guided by a pro-people militant activism that brought together strands of radical anti-imperial Pan-Africanism, Marxist-Leninism, feminism, agro-ecological approaches to food justice, and more. Through his electrifying public speeches, his militant activism materialised as one grounded in the urgent and on-going need for concrete decolonization—a revolutionary process that Sankara understood to be protracted, necessarily experimental (in this way, ‘mad’), holistic, and centred on the intellectual liberation of everyday African people, who would be responsible for their own empowerment. For Sankara, women and the rural poor were unavoidably at the forefront of liberation projects.

Thomas Sankara (1949-1987) was unique among late 20th century presidents in Africa and beyond. His political leadership was guided by a pro-people militant activism that brought together strands of radical anti-imperial Pan-Africanism, Marxist-Leninism, feminism, agro-ecological approaches to food justice, and more. Through his electrifying public speeches, his militant activism materialised as one grounded in the urgent and on-going need for concrete decolonization—a revolutionary process that Sankara understood to be protracted, necessarily experimental (in this way, ‘mad’), holistic, and centred on the intellectual liberation of everyday African people, who would be responsible for their own empowerment. For Sankara, women and the rural poor were unavoidably at the forefront of liberation projects.

As such, Sankara, throughout his short life (he was just 37 when he was killed), sought to create the structural and cultural conditions through which Burkinabè people would assert their own projects, ambitions, and goals. Central to this was an explicit distancing from the kinds of economic and social approaches to policy which were conventional in the late Cold War—including foreign debt, socio-economic imperialism, and international development aid. During the revolutionary project that he led in the West African country of Burkina Faso from 1983 to 1987, the revolutionary government pursued ambitious and autonomous large- and small-scale initiatives to promote heath and decrease hunger and thirst in the country. Among these initiatives: mass child vaccination projects, tree-planting and re-forestation initiatives and the construction of a railroad to connect the country’s main cities which was built through collaboration at the grassroots by citizen-workers (international financial institutions refused to back the project). Each of these initiatives was oriented to ensuring that each Burkinabè had ‘two meals a day and access to clean drinking water’.

For Sankara, racial, gender, ecological, epistemic, food and economic justice were intrinsically connected. Revolutionary projects are therefore necessarily holistic: there would be no end to hunger without an end to imperialism, he said. There would be no revolution without an end to women’s oppression, he said. There would be no end to deforestation without an emancipatory educational system that re-centred values drawing from the indigenous political orientation of burkindlum* which fostered self-respect, pride, and honesty.

The almost astonishing successes of the Burkinabè revolutionary project of the 1980s have received increased popular and scholarly attention in the last decade; this, after two decades of near-silence on and/or superficial and Eurocentric considerations of Sankara in scholarship written in English (there is a rich international scholarship on Sankara in French). The 15th of October 2017 marked the 30th anniversary of the assassination of Thomas Sankara and collective, popular ceremonies marking the moment were held in Burkina Faso, Canada, Italy and the US. Significant for such remembering of Sankara’s legacy is an awareness of the on-going absence of justice for his assassination alongside twelve of his collaborators. Sankara’s life and legacies remain critical for activists and young people organizing for justice today.

*Burkindlum is a Burkinabè political and ethical orientation that emphasises sacrifice, honesty and integrity in action. See Zakaria Soré (2018) “Balai Citoyen: A New Praxis of Citizen Fight with Sankarist Inspirations” in ‘A Certain Amount of Madness’: The Life, Politics & Legacy of Thomas Sankara, Murrey, Amber (ed.). London: Pluto Press.

Essential Reading (in English):

Sankara, Thomas (2007) Thomas Sankara Speaks. Pathfinder Press.

Harsch, Ernest (2014) Thomas Sankara: An African Revolutionary. Ohio University Press.

Murrey, Amber, ed. (2018) ‘A Certain Amount of Madness’ The Life, Politics, and Legacy of Thomas Sankara. London: Pluto Press.

Shuffield, Robin (2006) Thomas Sankara: The Upright Man. Documentary Film, 52 mins.

Further Reading (in English):

Battistoli, D.S. (2017) What Would A Sympathetic Critique of Thomas Sankara Look Like? Africa Is A Country.

BBC World Service, The Forum, “Sankara: An African Revolutionary,” December 2017.

Biney, Ama (2013) Revisiting Thomas Sankara, 26 Years Later. Pambazuka News.

Questions:

1. African feminist Patricia McFadden (2018) has argued that Sankara’s insistence in the importance of women’s emancipation in Africa was the most radical and dangerous element of Sankara’s revolutionary vision. Why might gender justice have been such a radical component of the revolutionary project?

2. Sankara’s memory burns strong in Africa today, where the project for decolonization remains unfinished. What lessons might his revolutionary leadership, militant presidency, and/or holistic approach to emancipation hold for other places in the world?

3. What does the slighting of the Burkinabè revolutionary project of 1983-87 and Sankara’s leadership in Anglophone scholarship reveal about the geopolitics of knowledge, in particular what does it reveal about the study of Africa more broadly?

Submitted by Amber Murrey. For questions, comments or other correspondence about Sankara, please contact: amber [dot] murrey-ndewa@aucegypt [dot] edu