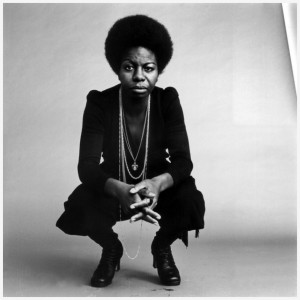

“I wish you could know what it means to be me, then you’d see, you’d agree, everybody should be free, ‘cause if we ain’t we’re murderous” (Nina Simone, Montreux 1976)

Nina Simone can be said to have lyrically theorised the ontological state of violence constituting America’s racial order, but more effectively, she took it to the stage and performed it. And beyond this, her most radically productive move on stage was to reverse the racial power relation and amplify it, discomfiting and alienating white audiences through a bodily authorisation of counter-violence.

Simone’s rigorous training in classical piano had allowed her to bring classical method, command, and counterpoint to the jazz world, but it had also given her the dream of becoming the first Black classical pianist (“and that was all that was on my mind, that was what I was prepared to be”). This dream was ruptured when she was turned down by the Curtis Institute for, she believed, being Black – a rejection which would become one of her life’s most formative moments politically.

She later kept company with James Baldwin, Langston Hughes, and Lorraine Hansberry (With Lorraine “It was always Marx, Lenin and revolution – real girls’ talk […] Lorraine started off my political education and through her I started thinking about myself as a black person in a country run by white people and a woman in a world run by men”). Her political consciousness was otherwise magnified by the profound events of her time – including the Alabama bombings of 1963 – a politicisation which she experienced biblically; “the Truth entered into me and I came through.”

Daphne Brooks, Malik Gaines and others have read Nina Simone as Brechtian in her mode of political performance. Drawing, for example, on ‘social gest’ Nina would subvert the broad range of cultural genres she drew on and play with irony as a form of critique. In renditions of violent and grief-ridden songs (Mississippi Goddam especially) she would adopt an incongruous up-tempo style (Gaines 2013). But she diverted from Brecht in the sense that she inverted his prohibitionary stance on emotion in performance; instead Simone engaged a highly politic form of affect. In the words of Gaines: “Rather than orchestrating an alienation effect to undercut emotional affect, Simone deploys an affect effect to assert herself in excess of her alienated possibilities.” Through her subversive performance of Feelings, for instance, what was “a bourgeois ballad of self-pity” becomes instead “a social action”. And she bookmarks this characteristic subversion with an incredulous Marxian comment on the material backdrop to such emotional lyrics: “I do not believe the conditions that produced a situation that demanded a song like that!”

Another of her classic interjections punctuated the gentle lyrical appeal of I wish I knew how it would feel to be free with a moment of honest anger anticipatory of later political statements of no justice, no peace: “I wish you could know what it means to be me, then you’d see, you’d agree, everybody should be free, ‘cause if we ain’t we’re murderous.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5dlrXCYrNYI

Gaines reads Nina Simone as performing a subjectivity which went beyond the ‘negative alienation’ of Du Boisian double consciousness; identifying instead an emancipatory ‘quadruple consciousness’, a multiple positionality which became a source of provisional power.

This positionality is indicated in Simone’s radical composition Four Women, which brings each of its female subjects into being through reference to her skin tone, then to the sexual power relation that either brought her into being or marks her existence (“whose little girl am I, why yours if you’ve got some money to buy”) and through an allusion to her labouring identity. This song builds an affective tension between the women themselves, the audience, and “Simone’s performing body” (Gaines 2013) and ultimately performed a disruptive raced and gendered consciousness making this exemplary of her most radical political work.

Essential reading:

Malik Gaines (2013) The Quadruple-Consciousness of Nina Simone, Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory, 23:2, 248-267

Simone, Nina with Stephen Cleary. 1991. I Put A Spell on You: The Autobiography of Nina Simone. New York: Pantheon Books.

Brooks, Daphne A. 2011. “Nina Simone’s Triple-Play.” Callaloo 34 (1): 176–197

Further reading:

What Happened, Miss Simone? 2015 Documentary by Liz Garbus

Brooks, Daphne A. 2006. Bodies in Dissent: Spectacular Performances of Race and Freedom, 1850– 1910. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Questions:

What was Nina Simone’s contribution to the politics of Black identity?

In what ways do gender and race interact in the work of Simone?

What critical methods did Nina Simone bring to political performance?

Submitted by Lisa Tilley