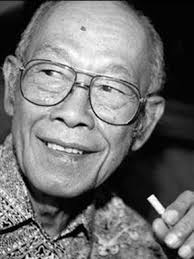

Pramoedya Ananta Toer is an Indonesian novelist, historian (noted for his works on Indonesian Chinese ethnicity and the history of revolution), as well as journalist. He was a political prisoner during Soeharto’s purge of the Indonesian Communist Party (1965-1978), having previously worked as Editor of Lentara, a cultural supplement of Bintang Timur, and was a prominent member of the communist-leaning People’s Institute of Culture (Lembaga Kebudayaan Rakyat/LEKRA). He was a productive writer, both before his arrest in 1965 and even after his release from jail in 1987. Even though Pramoedya was more renowned for his literary works, he has made a long-lasting contribution to Indonesian social and political thought, which could be categorized in three themes: (1) a rethinking of postcolonial identity; (2) a critique of nativism, colonialism, and authoritarianism; and (3) a contribution of Indonesian perspective of socialist realism in arts and literature.

Pramoedya Ananta Toer is an Indonesian novelist, historian (noted for his works on Indonesian Chinese ethnicity and the history of revolution), as well as journalist. He was a political prisoner during Soeharto’s purge of the Indonesian Communist Party (1965-1978), having previously worked as Editor of Lentara, a cultural supplement of Bintang Timur, and was a prominent member of the communist-leaning People’s Institute of Culture (Lembaga Kebudayaan Rakyat/LEKRA). He was a productive writer, both before his arrest in 1965 and even after his release from jail in 1987. Even though Pramoedya was more renowned for his literary works, he has made a long-lasting contribution to Indonesian social and political thought, which could be categorized in three themes: (1) a rethinking of postcolonial identity; (2) a critique of nativism, colonialism, and authoritarianism; and (3) a contribution of Indonesian perspective of socialist realism in arts and literature.

A rethinking of postcolonial identity

It is widely known that Pramoedya’s best work is his Buru Quartet: a tetralogy of novels written by Pramoedya during his imprisonment in Buru Island. Buru Quartet consists of four novels: This Earth of Mankind, Child of All Nations, Footsteps, and House of Glass. The novels centre upon the live of Minke, an educated Indonesian journalist who was involved in anti-colonial activism against Dutch colonialism in the early 20th century. The story was actually a novelized biography of Tirto Adhi Soerjo, a pioneer of journalism within the Indonesian modern anticolonial movement.

In the Buru Quartet, Pramoedya provides a different narrative of colonial/anticolonial dialectics as a complex historical process. He introduced two main protagonists as complex historical figures: Minke, a Javanese middle-class royal who studied in Dutch schools, and was involved in anticolonial journalism in the 1920s, and Nyai Ontosoroh, the concubine of an elite Dutch planter with no formal educational background. Pramoedya uniquely develop the story to capture the dynamics of colonialism. In Pramoedya’s narrative, colonialism was not a simply ‘colonized native’ versus ‘European colonizer’. By presenting the story of Minke, Pramoedya put forward a narrative of anticolonial struggle as a complicated process. Rather than a ‘good native’ versus ‘bad European’ project, anticolonial struggle in this reading was made possible through interactions between Europeans (of various political and moral orientations) with Javanese (also with variety of class and social strata).

As Hilmar Farid (2014) has aptly mentioned, Pramoedya “was a nationalist at heart”. He conceived of anticolonialism as a distinctly modern project, which emerged in a specific context that was shaped by Dutch colonial institutions (education, court, plantation, journalism, etc) but articulated against Dutch authoritarian politics of colonial administration. After all, the Buru Quartet illustrates a dynamic of postcolonial identity as an inherently modern project, but one embedded in early 20th century resistance against colonial authoritarian politics that repressed the popular forces.

A critique of nativism and the inevitability of social and cultural change

Understanding anticolonialism as a modern project, leads us to reconsider the assumption of ‘modernity’ in the concept of ‘postcoloniality’. Pramoedya depicts Indonesia’s postcoloniality as conceived as a modern project rather than one isolated from the emerging discourse of modernity that emerges in the 1920s Dutch East Indies, albeit a project which is reframed in a narrative that resists the authoritarian politics of colonialism. The key insight here relates to how the concept of colonialism is somewhat entangled with authoritarianism, and in that sense is reproduced even after independence.

A political prisoner himself, Pramoedya is heavily critical of Dutch, Japanese, and even Indonesian forms of colonialism (during Soeharto’s New Order) for their reproduction of authoritarian control, racialized bias, and repressive actions towards resistance. In his other works, most notably Arok Dedes and Arus Balik, Pramoedya puts forward a critique of hegemonic narratives of Javanese culture as harmonious, static, and conservative. Arus Balik provides the context of the Javanese polity as a dynamic project, emerging from a contestation between Islamic reformers and Majapahit conservative rule, in which the former proved victorious due to their ability to drive social transformation.

A political prisoner himself, Pramoedya is heavily critical of Dutch, Japanese, and even Indonesian forms of colonialism (during Soeharto’s New Order) for their reproduction of authoritarian control, racialized bias, and repressive actions towards resistance. In his other works, most notably Arok Dedes and Arus Balik, Pramoedya puts forward a critique of hegemonic narratives of Javanese culture as harmonious, static, and conservative. Arus Balik provides the context of the Javanese polity as a dynamic project, emerging from a contestation between Islamic reformers and Majapahit conservative rule, in which the former proved victorious due to their ability to drive social transformation.

In Arok Dedes, Pramoedya tells the story of Ken Arok, who mobilised popular support with deep political intrigues to take Tumapel from its local ruler, Tunggul Ametung. The novel narrated Javanese culture as not necessarily harmonious or static; it also involved conflict and political intrigues in a very blunt way. In Arok Dedes, Pramoedya depicts Ken Arok as a popular leader, who led the people to resist the authoritarian rule of Tunggul Ametung and organized an alliance between various social forces at that time –Brahmana (priest), trade merchants, slaves, and even gangsters. In both works, Pramoedya narrated the inevitability of social and cultural change that is underpinned by resistance and real politics in a local context.

Contextualising socialist realism in Indonesian history

As Eka Kurniawan (2001) has noted, Pramoedya’s epistemology could be traced to what was known as ‘socialist realism’ in Indonesian arts and literary discourse. Socialist realism contextualises history and class struggle in the form of arts and literary works. For Pramoedya and his Lekra fellows in the 1960s, literature can be a form of political struggle. According to Eka, Pramoedya was inspired by Maxim Gorky’s theory, “people must know their own history.” Literary works inform ordinary people of history, provide messages to strengthen people’s struggles, and mobilise a literary struggle against the oppressive structures in society. What makes Pramoedya’s works unique is his historical contextualisation of literary works. As noted above, his Buru Quartet was informed by a history of Raden Tirto Adhi Soerjo, an Indonesian journalist who pioneered journalism against Dutch colonialism in the 1920s, and he undertook substantive historical research when writing Arus Balik. In his early work, Korupsi, he launched a staunch critique of the corrupt practices of bureaucrats during the Soekarno era, and Perburuan is heavily influenced by the revolutionary struggle between 1945-1949.

Overall, Pramoedya’s work provides an inevitable entanglement between literature, history, and the forms of resistance he often portrayed in his works before and after his imprisonment in Buru. His works also bring to the fore questions of what can constitute social and political theory.

Essential Reading (English):

The Buru Quartet:

Toer, Pramoedya Ananta. This earth of mankind. Vol. 1. Penguin, 1996.

Toer, Pramoedya Ananta. Child of all Nations. Vol. 2. Penguin, 1996.

Toer, Pramoedya Ananta. Footsteps. Vol. 3. Penguin, 1996.

Toer, P.A., 1997. House of Glass (Vol. 4). Penguin.

Toer, P. A., (1999). The Mute’s soliloquy: a memoir. Hyperion Books (translated and edited by Willem Samuels).

Further Reading

Toer, Pramoedya Ananta, and Christopher Lloyd GoGwilt 1996. “Pramoedya’s Fiction and History: An Interview with Indonesian Novelist Pramoedya Ananta Toer.” The Yale Journal of Criticism 9.1: 147-164.

Toer, Pramoedya Ananta, Andre Vltchek, and Rossie Indira 2006. Exile: Pramoedya Ananta Toer in Conversation with Andre Vltchek and Rossie Indira. Haymarket Books.

Setiadi, Hilmar Farid 2014. Rewriting the Nation: Pramoedya and the Politics of Decolonization. PhD Thesis, National University of Singapore.

Kurniawan, Eka 2002. Pramoedya Ananta Toer dan sastra realisme sosialis. Penerbit Jendela.

Foulcher, Keith 1981. “”Bumi Manusia” and” Anak Semua Bangsa”: Pramoedya Ananta Toer Enters the 1980s.” Indonesia 32: 1-15.

Sajed, Alina 2017. “Peripheral modernity and anti-colonial nationalism in Java: economies of race and gender in the constitution of the Indonesian national teleology.” Third World Quarterly 38.2: 505-523.

Scherer, Savitri Prastiti 1981. “From culture to politics: the writings of Pramoedya A. Toer, 1950-1965.” PhD Thesis, Australian National University.

Questions:

What is the significance of Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s literary works for our understanding of postcoloniality and postcolonial identity, beyond Indonesia’s historical context?

Discuss the importance of Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s work for International Relations and broader questions related to postcolonial IR theory.

How does Pramoedya build on and contextualise socialist realism in his specific experience of authoritarianism and revolutionary struggle against colonialism in Indonesian history, and what could we learn from that in the global context?

What is the relationship between resistance, literary, and social theory for Pramoedya?

Other Notable Works by Pramoedya:

Kranji-Bekasi Jatuh (“The Fall of Kranji-Bekasi”) (1947)

Perburuan (The Fugitive (novel)) (1950)

Keluarga Gerilya (“Guerilla Family”) (1950)

Bukan Pasar Malam (It’s Not an All Night Fair) (1951)

Cerita dari Blora (Story from Blora) (1952)

Gulat di Jakarta (“Wrestling in Jakarta”) (1953)

Korupsi (Corruption) (1954)

Midah – Si Manis Bergigi Emas (“Midah – The Beauty with Golden Teeth”) (1954)

Cerita Calon Arang (The King, the Witch, and the Priest) (1957)

Hoakiau di Indonesia (Chinese of Indonesia) (1960)

Panggil Aku Kartini Saja I & II (“Just Call Me Kartini I & II”) (1962)

Gadis Pantai (Girl from the Coast) (1962)

Nyanyi Sunyi Seorang Bisu (A Mute’s Soliloquy) (1995)

Arus Balik (Turning of the Tide) (1995)

Arok Dedes (1999)

Mangir (1999)

Larasati (2000)

Perawan Remaja dalam Cengkeraman Militer: Catatan Pulau Buru (2001)

Submitted by Ahmad Rizky M. Umar