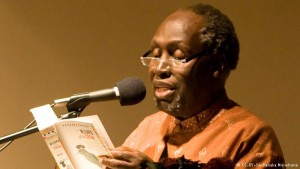

Ngugi wa Thiong’o is a Kenyan novelist, playwright and literary critic. His novels include Weep Not, Child (1964), The River Between (1965), A Grain of Wheat (1967), Petals of Blood (1977) and Devil on the Cross (1980). The main themes that he focuses on are the legacy of colonialism, traditionalism, cultural nationalism, and the role of the intellectual in the postcolony. His works navigate the colonial and postcolonial contradictions of Kenyan and Gikuyu society and the tensions between modernity and the past.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o is a Kenyan novelist, playwright and literary critic. His novels include Weep Not, Child (1964), The River Between (1965), A Grain of Wheat (1967), Petals of Blood (1977) and Devil on the Cross (1980). The main themes that he focuses on are the legacy of colonialism, traditionalism, cultural nationalism, and the role of the intellectual in the postcolony. His works navigate the colonial and postcolonial contradictions of Kenyan and Gikuyu society and the tensions between modernity and the past.

He has also written extensively on the role of language and the relationship between literature, culture and politics. These writings have been collected in various publications: Homecoming (1972), Writers in Politics (1981), Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature (1986). He argues that language is a vehicle for continuing the subjugation of peoples.

The question is this: we as African writers have always complained about the neo-colonial economic and political relationship to Euro America. Right. But by our continuing to write in foreign languages, paying homage to them, are we not on the cultural level continuing that neo-colonial slavish and cringing spirit? What is the difference between a politician who says Africa cannot do without imperialism and the writer who says Africa cannot do without European languages? (wa Thiong’ o 1986: 26)

Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s decision to write in Gikuyu demonstrates the centrality of language in his thoughts. Writing in Gikuyu, he argued, ‘a Kenyan language, an African language, is part and parcel of the anti-imperialist struggles of Kenyan and African peoples’ (wa Thiong’o 1986: 28). Moreover, he wanted to write for the very subjects to whom through his novels he was attempting to give agency: peasants and the working class.

The Great Nairobi literature debate that focused on the teaching of literature and how it should be organized also raised important questions with respect to the perspective through which education is organized. Henry Owuor-Anyumba, Taban lo Liyong and James Ngugi wrote a memo titled ‘On the Abolution of the English Department’ on October 24, 1968. The memo was written as a reply to a letter by James Stewart (Acting Head of the Department of English), which proposed curriculum reform. The memo argued that according to the proposal ‘the English tradition and the emergence of the modern west is the central root of our consciousness and cultural heritage. Africa becomes an extension of the west’ (wa Thiong’o 1972: 146) Thus, the main question they raised was ‘if there is a need for the ‘study of the historic continuity of a single culture, why can’t this be African? Why can’t African Literature be at the centre so that we can view other cultures in relationship to it?’ (wa Thiong’o 1972: 146) These debates also raised important questions with respect to the role of the university and to what extent the debate was challenging the role of the university. Thus, ‘by seeking to substitute the romantic discourse of authentic Africanness for the discourse of ‘alien’ Englishness as the condition for literary education in the university, the Nairobi Revolution paradoxically reaffirmed the traditional ideology of English literature’ (Amoko 2010: 4-5). Furthermore, the role of the postcolonial university ‘a discursive formation whose links to the metropolitan university are more fundamental and enduring’ was not directly addressed (Amoko 2010: 5).

The Great Nairobi literature debate that focused on the teaching of literature and how it should be organized also raised important questions with respect to the perspective through which education is organized. Henry Owuor-Anyumba, Taban lo Liyong and James Ngugi wrote a memo titled ‘On the Abolution of the English Department’ on October 24, 1968. The memo was written as a reply to a letter by James Stewart (Acting Head of the Department of English), which proposed curriculum reform. The memo argued that according to the proposal ‘the English tradition and the emergence of the modern west is the central root of our consciousness and cultural heritage. Africa becomes an extension of the west’ (wa Thiong’o 1972: 146) Thus, the main question they raised was ‘if there is a need for the ‘study of the historic continuity of a single culture, why can’t this be African? Why can’t African Literature be at the centre so that we can view other cultures in relationship to it?’ (wa Thiong’o 1972: 146) These debates also raised important questions with respect to the role of the university and to what extent the debate was challenging the role of the university. Thus, ‘by seeking to substitute the romantic discourse of authentic Africanness for the discourse of ‘alien’ Englishness as the condition for literary education in the university, the Nairobi Revolution paradoxically reaffirmed the traditional ideology of English literature’ (Amoko 2010: 4-5). Furthermore, the role of the postcolonial university ‘a discursive formation whose links to the metropolitan university are more fundamental and enduring’ was not directly addressed (Amoko 2010: 5).

His latest publication has been In the House of the Interpreter (2012) the second volume of his memoirs (the first volume was titled Dreams in a Time of War (2011)). The House of the Interpreter recounts the years between 1955- 1959 and his memories of being at the Alliance High School. The memoirs are an important window into the development his thought and his growing disillusionment with the system. One of his memories from the school focuses on the tensions with his teachers;

His latest publication has been In the House of the Interpreter (2012) the second volume of his memoirs (the first volume was titled Dreams in a Time of War (2011)). The House of the Interpreter recounts the years between 1955- 1959 and his memories of being at the Alliance High School. The memoirs are an important window into the development his thought and his growing disillusionment with the system. One of his memories from the school focuses on the tensions with his teachers;

One day Principal Smith, our literature teacher, dwelled on our tendency to use big words to suggest a profound grasp of the language. [..]Avoid words with Latin roots, he told us. Use the Anglo-Saxon word. Above all, learn from the Bible. It has the shortest sentence in English. Jesus wept. Two words. So follow the example of Jesus. He spoke very simple English.

I was puzzled. Not trying to be clever or correct him, I raised my hand and said that Jesus did not speak English: the Bible was a translation. (wa Thiong’o 2012: 22-23)

ESSENTIAL READINGS:

wa Thiong’o, Ngugi (1981) Writers in Politics. Exeter, N.H: Heinemann.

wa Thiong’o, Ngugi (1986) ‘The Language of African Literature‘ Decolonising the mind: The politics of language in African literature. London: James Currey.

RECOMMENDED READINGS:

Gikandi, Simon (2000) Ngugi Wa Thiong’o. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Amoko, Apollo Obonyo (2010) Postcolonialism in the Wake of the Nairobi Revolution. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

wa Thiong’o, Ngugi (1972) Homecoming. Exeter, N.H: Heinemann.

QUESTIONS:

What is the role of language in reproducing systems of oppression and exclusion established during colonialism?

Were the interventions of the Nairobi literature debate sufficient in decolonizing the university? What further strategies could be developed?

How do we enter into dialogue with the subjects to whom we aim/claim to give agency to in our writings?

Submitted by Zeynep Gulsah Capan